City under the map

At night, the city plays a different tune. The facades quiet down and the cobblestones underfoot take on a springiness, as if breathing. Lena Nocuń liked this hour, just after midnight, when the world folds up for sleep and she can lay out her books, glues and brushes in her basement studio without feeling that someone is about to stand in the doorway and ask about things for which she has no answers.

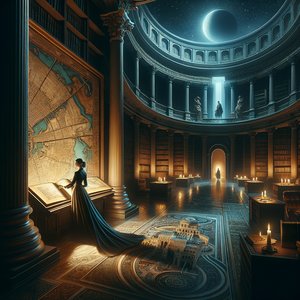

The conservation studio was underneath the specialised cartography reading room - a wide, luminous rotunda with a mosaic of maps on the floor and a vault of milky glass. The day was full of hands and questions. The night belonged to Lena and the paper that rustled like waves. That evening, a package was waiting for her - a rectangular box of raw cardboard, tied with red string. On the back someone had nailed a wax seal with a wind rose motif, the needle of which was exaggeratedly long and thin, like a gramophone needle.

She didn't order anything. No one had warned about the deposit. Yet the seal was with the museum's logo, and the label bore her name. Lena washed her hands, slipped her finger under the string and slid it out slowly, as if she were untying a ribbon at someone's birthday party.

Inside lay an atlas. The leather on the cover was the colour of wet coffee, with a distinct nerve. There were brass fittings woven into the corners, into which someone had woven a delicate pattern resembling tiny scales. As she leaned closer, she smelled ozone and salt. Silly, she thought, smells can seep into the imagination. She slipped her fingernail under the age and lifted it.

The paper was not the paper she knew. The pages had a slightly metallic sheen, but did not reflect the light; rather, they diffused it, as if each page had a ground mist in it. On the title page, in fine, slanted writing, it read: "Atlas of Passages". No author's name, no year, no publisher.

- Great," muttered Lena. - Either a diversion or a joke.

She turned the page. On the first map she recognised her town, though not immediately. The streets were thin as veins, the squares widened, the river someone had routed whimsically, as if by wind. The strangest thing, however, was the silvery thread running through the centre - it resembled no familiar artery. From the point where the library stood, it spun downwards like the outline of a path that one draws under the skin with a fingernail.

In the margin, again in the same slanted script, it stood: "opens at thirteen minutes past midnight". Underneath, someone had placed a dot so heavy that it pierced the paper and left a mark on the next page.

Lena pushed back her chair and walked over to the window, from where a section of the rotunda could be seen. On the floor mosaic, in place of the wind rose, children sometimes sat - during the day, when the sun broke on the glass and made luminous spots on the floor. Now the mosaic was dark, even, with only the metal wires under the glass gently buzzing when a night tram passed through the city.

She glanced at her watch: 00:07, enough to brew a cup of tea and decide that maybe she would wait after all. The water in the kettle whined quietly, like a miniature world locomotive. Lena poured over the leaves, rubbed her hands into her apron and went upstairs, carrying the atlas carefully like a child.

The rotunda was chilly at this hour. The milky glass of the ceiling had a tinge of dusted ice. She leaned the album against the edge of the table and unfolded it by the mosaic itself. The smell of stone and old books came from the side of the stairs. The watch on her wrist flashed: 00:12. Lena smiled to herself, uncertain whether she was laughing at the absurdity of the moment or at her own willingness to believe in the absurdity.

As the second hand stopped at the number twelve and jumped to thirteen, something happened that had the logic of snow in it: impossible and yet innocent. The silver thread on the map flashed, so quietly that Lena wasn't sure if it was the light or her pulse. At the same moment, the mosaic on the floor beneath the twitching wind rose shook. The stones that formed the contours of the continents began to separate, each as if remembering where to be and where not to be.

- 'No,' Lena said in a whisper. - No, no, no.

And yet she stood motionless, watching as a crack appeared in the centre of the rotunda - not like a crack, but rather like an open eye. From the depths blew air with the smell of rain that had not yet fallen. A distant murmur came from below, something between a splash and the whispering of a crowd out of sight.

Lena touched the cover of the atlas. The skin twitched under her fingers, slightly, like the skin of an animal trying to ignore a fly. She swallowed her tea, which suddenly turned metallic. She glanced at her watch again, as if checking the time could undo what had already happened. 00:14.

The gap widened and showed the steps. They were of black stone, so smooth that they reflected the mosaic like an alien sky. On the side, in the wall, metal handles blossomed. Everything took exactly as long as it needed to - like a mechanism that had been screwed on a long time ago and now finally got going, without complaint, without stammer.

The phone in her pocket vibrated. Lena pulled it out reflexively, thinking maybe the night guard, maybe Paul - the one who usually called at meaningless times to ask a single sentence like: "Have you heard that the sound in the water is not the same as the sound in the air?".

The contact sheet had no name. Only the title: 'Grandma - recording'. Lena had no right to have such an entry. Her grandmother had died when Lena was in high school, and she had never left a message. Yet the screen confidently displayed words she couldn't ignore. She pressed "play".

"Lena," - came a soft, husky whisper - "if you go, don't be greeted with a name that's not yours. Look at the direction, not the destination. And remember - there are things that look like a road but are just a sight."

The voice broke off as suddenly as if someone had cut the thread. The phone went off. Lena touched the button, to no avail. The screen reflected the steps - black, inhuman, tempting like a mirror in which one would like to see if one had a face.

She drew in a breath of air. She wasn't in the habit of listening to recordings she didn't understand, or stepping into gaps that weren't noted in the evacuation plans. Yet the calm she felt was not of the sensible kind. It was like the quiet after a substantial rain - everything is still wet, but you know you can go barefoot.

She slipped the bag off her shoulder and put the atlas inside, which closed on its own as if it had fallen asleep. She rested her hand against the cold metal of the handrail and descended the first step. The stone under her shoe was out of this room, it had the chill of a cellar where no one turns off the light because they never turn it on. The second step, the third, the fifth - each like a decision that cannot be undone. Overhead, the mosaic closed silently, leaving behind only a circle of light that quickly diminished until it became a point and disappeared.

The night might have lasted, or it might not have existed. The narrow corridor widened and opened into a space that could not be measured by sight. In front of Lena stretched a bank, but it was not sure what: the water lay below like the skin of a black animal, breathing steadily. On the other side stretched something like the sky - uninverted, dark, full of stars that pulsed faster than they should. Sometimes they collided and faded, like drops of mercury.

Below the ceiling, where she would have expected a vault, strands of light hung. They floated down like plankton, stopped just above the water and floated up again. Each thread ended in a tiny ball that was illuminated by a pulse, like a breath. Lena reached out her hand. One of the beads touched her skin and moved like a gentle spark. Her fingernails became transparent for a moment, and she saw thin threads inside - as if her fingers were a map of tiny rivers.

- 'Exaggeration,' she said to herself, in a half-hearted voice to tame the sound of her own speech. - Don't fantasise.

The landscape did not respond. But somewhere to her left, beyond the low stone threshold, Lena heard something that might have been a movement. Not a step - rather a shift of weight, as if someone had placed a lantern and moved it. The light vibrated and cut through the air in a narrow arc.

Lena clung with her back to the cool rock. Her heart played with a pace she hadn't felt in herself for a long time - neither when working with delicate engravings nor when putting super-valuable specimens into the hands of researchers. Was it a feeling from another era of life, from childhood? When you open a wardrobe and take a step into the depths, because you hear that there is a 'next' there.

From an alcove on the opposite side crawled the first lamp - an open lantern without glass, in which burned a flame of a strange colour: milky, yet dense. The light produced no smoke. It moved gently, as if combed out of the air. Behind the lantern, a silhouette appeared - tall, in a cloak with long sheaths that almost brushed the stone. She moved unhurriedly, taking steps where there were no steps, yet she did not fall. Where she rested her foot, a mark was left for a moment, like a wet mark on glass. And that mark glowed for a split second before blending into the darkness.

Lena felt her bag get heavier. She lifted the flap and looked in. The atlas was not lying inert. It was open, even though she hadn't opened it, and the pages were arranged in a fan shape. The lines of shores, rivers and streets trembled. On the inside cover she saw her name, written in the same slanted hand: "Lena Nocuń". Below, crossed out, was another: "Elena N.". The ink was still wet.

The silhouette with the lantern paused at the border between light and shadow, as if it had decided that this was the right place to talk without words. The lantern twitched. For a moment it seemed as if someone had lifted the sky like a curtain: the stars swirled, arranged again in a pattern - a wind rose, exactly like the one in the mosaic, only with an excess of needles, inconceivably many. One of them pointed straight at Lena.

In her pocket, although the phone was dead, something trembled - not a vibration, more like that soft, circular feeling when a train passes in a tunnel that cannot yet be heard. Lola, the cat from the flat above Lena, sometimes warned of storms like this. Now the air had become similar: electrified, ready to speak.

- 'Lena,' said a voice. It was not from her pocket. Nor was it from a silhouette with a lantern. It sounded as if it came from many places at once, but most powerfully from the part of the rock against which she was leaning her back.

She froze. The voice spoke her name the way it had been spoken by someone who remembered when she was four years old, how she got angry that her socks were too short, and how she learned to fold paper boats out of newspaper. There was nothing threatening about it, yet every fibre in the back of her neck trembled.

- 'Leno,' he repeated. - 'You're late.

The silhouette with the lantern raised his hand. At the same moment, a second light answered from the darkness on the right - from a place where nothing should be -. The lamps faced each other like two visions of the same road. The stone steps beneath Lena's feet moved minimally, like keys waiting for someone to pick a tune.

The atlas in the bag unfolded the cards and - though Lena didn't touch them - shifted them, arranging a sign she knew all too well from the edges and shadows. A sign she had once promised herself never to read again. The lights moved a step closer, simultaneously.

Autor zakończenia:

English

English

polski

polski

Co było dalej?

Co było dalej?