The Map That Drew Back

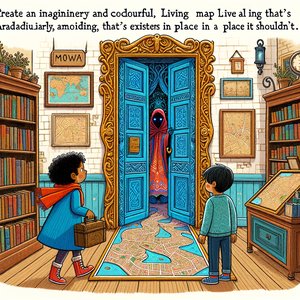

The bell above the door of Pilcrow & Sons Cartography was shaped like a silver compass needle, and when Maya pushed the door open, it didn't jingle so much as hum. The shop smelled like rain on warm pavement and the inside of a book, and the dust in the air floated in lazy, sunlit specks as if it had been given the afternoon off.

Maya paused on the worn rug, taking in the shelves that slouched under the weight of rolled charts and the tall drawers labelled with brass plates: WORLD (Incomplete), STARS (Best Guess), OCEAN (Uncooperative), and-in the lowest, nearest to her sneakers-INACCURATE. She was eleven and liked patterns so much that she collected them: looping cloud edges, the ripple of pigeons taking off, the way a row of houses could look like teeth. Her little brother, Theo, ten and always ready to count things, tapped the floorboards with his toe and whispered, "Forty-seven, forty-eight, forty-nine..."

"You can count the maps if you run out of floorboards," Maya said, but she smiled. Theo dug a magnifying glass from his pocket like it was a favourite coin and held it up to the brass label.

The only other sign of life was a handwritten note propped against the register: Back soon-please don't file the mountains. A clock on the wall politely ticked through seconds that didn't seem to agree with the light outside. One window looked onto Hill Street, where summer leaned on the town of Wrenfield as if it meant to stay all week.

Theo was already crouched by the lowest drawer, because of course he was. "Inaccurate," he read, as though he were tasting the word. "Why would anyone keep wrong maps?"

"Maybe because getting lost is interesting," Maya said. But she glanced over her shoulder anyway before she knelt to help him pull. The drawer stuck, then sighed, and slid open with the soft snare-drum sound of paper on wood.

Inside lay a single roll wrapped in faded blue cloth and tied with twine, like a very polite present. A tag sat on top, weathered and thin. Return if found, it said in ink that had bled at the loops and tails. The moment Maya touched the tag, the compass bell swayed without anyone going through the door.

"We found it," Theo whispered. "But we didn't lose it."

Maya untied the twine and unrolled the cloth. The map inside was large, crisp, and edged with a border of tiny creatures with feathered tails, each holding a little banner. The banners said things like Here Be a Fence You Didn't Notice and This Field Smells Like Daisies and Bread. In the bottom corner, written in neat, small letters, was a legend:

Key: Lines may change their minds. Fold to find. Ink follows footsteps.

"Lines may change their minds?" Theo read, delighted. He pressed the magnifying glass to the paper and breathed a fog on it. The map showed Wrenfield-streets, the clock tower, the river's curl-but some names were wrong in the way dreams are wrong. The clock tower was labelled Mechanical Sunflower. The river was the Thread That Went For a Walk. And there, near the top, was their house, but the window of Maya's bedroom had a tiny arrow pointing at it which said Maya: light after midnight again?

"Okay, that's private," she muttered, but she was smiling as she traced their sidewalk with one finger. The ink didn't smear. It shivered.

Theo's magnifying glass clinked gently against the paper as he leaned closer. "Maya," he said quietly. "It's moving."

She held her breath. The street behind the Peppercorn Bakery-an empty space in real life, just a weedy lot where the old billboard had fallen-began to darken with new lines. A slender curve etched itself into the map in tiny dashes, stitches sewing a new path from nowhere to the edge of the millpond. Ink dots gathered like minnows, then formed letters. They spelled: Thirteenth Turn.

"There's no Thirteenth Turn," Maya said at once. Wrenfield had twelve numbered turns that hairpinned up the hill towards the tower, and everyone joked about it. If there had been a Thirteenth, someone would have made a cake about it by now. She glanced around the shop, half-expecting someone to be watching them and laughing.

No one was. The clock ticked its own opinion, unbothered.

Under the new street, so small it was almost a whisper, the map printed another line: Fold along dotted friend.

"Not a line," Theo said with satisfaction. "A friend." He tapped what she had missed: a faint string of dots running from the bakery corner to the riverbank. The dots were tiny enough to be shy.

"It's a trick," Maya said, but her stomach felt like it does when you're on a swing and someone pushes a little harder than expected. She pinched the paper, careful and neat, and folded along the dotted friend, aligning the bakery with the edge of the pond, bringing the ends of the town together. As the fold settled, the shop seemed to breathe in and hold it. The compass bell quivered; the light shifted a hair closer to evening.

Theo looked up. "Did it get darker?"

"Maybe the sun changed its mind," Maya said. But the hairs on her arms had lifted. She unfolded the map and found that where the fold had kissed the paper, the tiny creatures in the border had turned their heads to look-at them.

On the map, a new symbol blinked into being near Thirteenth Turn: two ink figures, drawn with a handful of quick strokes-one with a ponytail and a smudge of ink on the knee, one with a magnifying glass and untied laces. Above their ink heads appeared their names, lettered as neatly as if by a careful aunt: Maya. Theo.

"No way," Theo breathed. "No way no way no way."

Maya swallowed. "Coincidence," she said, although the map's corner felt warm under her palm. "Let's go look."

They slid the map back into the blue cloth and tied the twine with unsteady fingers. Maya tucked the bundle into her backpack and left the drawer open because it seemed wrong to pretend they hadn't done anything. The note by the register watched them, but didn't object.

Outside, the day lay over Wrenfield like a cat on a keyboard-comfortable, slightly heavy, and humming. The clock tower loomed up Hill Street, its hands inching towards four, and the peppery smell that wrapped the bakery was crossed with something softer, like cinnamon when it forgets to be loud.

They cut across to the weedy lot behind Peppercorn Bakery, through the loose slats in the fence that had been loose since forever. The weeds had grown to shoulder height and made a papery sound against their jeans. Somewhere, a bee had found a reason to be delighted.

Theo stopped. "Maya."

She saw it then, and even though she had been trying to expect it, she hadn't. A narrow path of pale stones stitched its way through the lot-the same curve she had seen stitch itself on paper. The stones weren't there yesterday; she would have noticed. Maya noticed everything that made a pattern hiccup. At the path's end stood a free-standing door, alone in the weeds.

It was the colour of a morning sky just before the sun figures itself out. A number plate read 13½ in silver. Instead of a knob, it had a brass handle shaped like a question mark that had decided to be polite and straighten up. A mail slot held a single thin card with a corner bent, as though it had been nibbled by time.

Theo edged closer. "What if it's for someone else?"

"It is for someone else," Maya said, and reached for the card. The brass was warm. She turned the card over. Deliver by 4:13, the front said. On the back, in small, tidy script, their names again: Maya and Theo.

Her heart gave one hard thud. She glanced up at the tower. Four o'clock chimed once, twice, three times, a fourth, the sound washing down the hill like silver water.

"It knows our names," Theo whispered, thrilled and a little frightened, the way you feel when you stand at the first step of a high dive.

Maya pulled the map back out, balancing it carefully on her knees so the wind wouldn't make any decisions for it. The paper unfurled and, like a good dog, settled where she wanted it. On the face of the map, their ink selves stood at a tiny blue door labelled 13½. The legend had shifted: Folded places fold other things.

"It's like... when you fold a paper crane and the bird appears where there wasn't one," Theo said. He was grinning now, because he loved when the world behaved like a puzzle that wanted you to solve it.

Maya studied the path, the door, the card. Her careful part said this was strange; her curious part said strange was simply a shape you hadn't learned the name for yet. She sighed and set the card in the pocket of her backpack. "We at least knock," she said. "Or we'll never stop wondering."

Theo nodded, then caught her sleeve. "Wait. Listen."

The lot was full of small sounds-flies that couldn't be bothered to land, the quiet gab of leaves. Under those, something else: a low mechanical whir, like a toy train somewhere far away, and a soft tick like a clock that lived under the floor. From the inch-high gap at the bottom of the door (because even doors that stand alone have to breathe), a ribbon of warm air spilled out that smelled like fresh bread and summer storms.

Maya reached out and wrapped her hand around the brass handle. It was warmer now, almost the temperature of a helpful hand. A faint vibration traveled through her fingers, like the purr of a cat that didn't want to admit it needed you.

On the map, printed in new ink that shone a little until it dried, a phrase unfurled near the door: When ready, someone will be too.

"Okay," Maya said, and her voice wobbled once but then flattened into a line she could walk on. She knocked, three times, polite.

For a breath, nothing happened.

Then, from the other side of the door-somewhere that should have been only weeds and sky-came three answering taps, as if knuckles had rapped on the inside wood in exactly her rhythm. The brass handle warmed again under Maya's palm, and the silver 13½ on the plate gave a small, noncommittal quiver.

Theo's eyes were huge. "Did you-did it-"

Maya squeezed the handle. The tiny latch somewhere inside the door made the smallest sound in the world, the click of a thought deciding. The card in her backpack shifted against the fabric as if nudged by a breeze that wasn't there. The path behind them seemed to draw closer, stones listening.

The handle turned a fraction on its own.

Autor zakończenia:

English

English

polski

polski

Co było dalej?

Co było dalej?