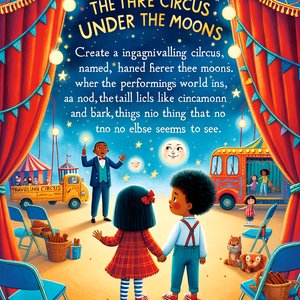

The Three Moons Circus

The circus arrived in the morning, when the cobblestones on the market square were still wet after the night's rain, and three moons were swaying in the puddles: the real one, the one reflected in the river and the third one, painted in chalk on a fresh placard. On the placard, swirling letters formed the name: 'Circus under the Three Moons'.

Nela stood in front of the placard with her nose so close that she could almost feel the chalk dust. Next to her, Oskar hopped on his toes, trying to spot the coiled coloured ropes and shiny hoops through the bars of the trucks.

- Can you imagine? - whispered Nela. - If the ropes really did lead to the moon.

- 'And I'd rather they led to candyfloss,' replied Oskar, but his eyes sparkled as if he was also thinking about ropes.

By midday, a tall tent with red and white stripes stood in the square. It smelled of roasted nuts and cinnamon, and the wind rang the metal flags like little enchanted bells. A wooden clown crooked at the entrance with a painted smile as wide as a bridge. The circus director stood at the box office, wearing a lilac cylinder and a tailcoat in dark, shimmering green. The cane he held had a star on the end, as if made of gold paper.

- Welcome, wanderers of heaven and earth! - he called out when he saw Nela and Oskar. - I am Alfons Basil, director of the Three Moons Circus. Do you dare to look where laughter meets silence?

Oskar nodded his head so fast that his hair danced. Nela smiled at the director and accepted the two programmes printed on thick, cream-coloured paper. On the first page were golden letters: "Mrs Luna's Juggling Flames", "Bruno's Cloud Collector", "Orchestra Without Instruments", "Mr Hector and the Dogs Who Sing".

- An orchestra without instruments? - muttered Oskar, immediately trying to imitate a trumpet with his mouth. - Then how do they play?

- You will find out in a moment," replied Alphonse Basil with a mysterious smile and winked at them. - Seats in the third row, on the left, where you can see closest to the sky.

Inside the tent, the light was soft, as if through milky glass. The sand in the arena smelled of fresh sawdust. At the back, spectators whistled and laughed, and in the orbit of the bright spotlight, dust danced like gold pollen. Nela looked around: at the top were stretched thick ropes like a spider's web, here was attached a swaying trapeze, and there, in the very centre of the dome, shone a small silver star, as if someone had tied a piece of sky to the tent. Oskar poked it with his elbow.

- 'Oh there! Do you see it? - He pointed to a narrow wooden platform high above the arena. - How do they get up there without a ladder?

Nela shrugged her shoulders, although she felt a pleasant shiver inside. Invisible passages always sounded interesting.

The main light went out, the first snare drum sounded, and then - as if someone had turned a page in a big book - Ms Luna appeared. Her juggling of flames turned out to be a juggling of skylights enclosed in glass bubbles. With each successive bubble, the air smelled of a forest night. The Orchestra Without Instruments 'played' the storm - one clown whistled the wind, two acrobats tapped their fingers on a wooden box as if it were a snare drum of rain, and Director Basil made the thunder quiet with a hand gesture. Mr Hector and his dogs really sang; they had colourful scarves and voices so harmonious that the audience laughed and clapped before they even finished.

In the interval between numbers, Nela noticed something that didn't fit in with the frosted, soft-as-wool setting. Above the arena, on a beam, someone had left chalky footprints - very tiny, as if a child had stepped on the ceiling. On the sand, just at the edge, stood an empty chair, into which a ray of light bites from time to time, as if waiting for someone's face. Oskar also looked up.

- 'I didn't see anyone go in there,' he whispered. - And it was swaying.

The trapeze, which had been asleep before, now swayed gently, although there was no draught in the tent. The drummer in the orchestra tapped a short, nervous note, and fell silent, as if frightened by his own rhythm.

Alphonse Basil returned to the arena, grunted and smiled broadly. This time, however, his smile did not reach his eyes, as if there, far away, something was distracting him.

- 'Dear spectators,' he began quietly, and the murmur died out like a fading bonfire. - Before we continue on our journey of laughter and breath, allow me to announce a number which is not on the programme. A number that only happens when three moons are looking in the same direction.

The audience murmured. Nela quickly unfolded the programme in her lap. She ran her finger over the golden letters. Nothing about an extra number. Oskar also glanced up.

- Maybe it's a surprise? - he whispered. - Like the cake in the box that no one talks about but everyone hopes is there.

- Or... - Nela broke off as she noticed something else. On the inside of the programme, where there had previously been a clean sheet of paper, a fine line flashed. It was as if someone had drawn with a brushhair a thin thread running from the bottom corner to the very top of the page. Next to it appeared two words, clear as breath in winter: 'Don't look down'.

- Did you see that? - Nela poked Oskar.

- 'That's some kind of joke,' he hissed, but he didn't take his eyes off the glowing thread either.

- Silence, please - Alphonse Basil raised his cane, and the sound of its tip tapping against the arena sounded sharper than usual. - It's time for the Walk on the Thread That Isn't There.

The spotlights twisted like the heads of curious birds. All the coloured lights went out, only one remained, a cold white one that climbed up the bamboo poles and stopped very high up where there was nothing - no ladder, no gangway, no man. Just air and a silence so attentive that you could hear someone in the audience opening a candy cane.

Nela lifted her gaze. The luminous thread on her programme moved slightly, as if responding to the movements of the spotlight. Oskar, who usually did not stop whispering, was now silent and his fingers tightened on the chair railing.

Somewhere above them the air rustled, as if something soft had touched an invisible fibre. The trapeze vibrated again, this time decisively. On the sand near the edge of the arena, dust rose in a fine circular vortex and fell, drawing the shape of a foot, like imprints on the wet sand by the river.

- 'He's joking, isn't he? - choked out someone from the row in front of them. - 'It's a projection, isn't it?

No one answered as the drums began quietly, evenly, like a heart that refuses to betray itself. High up in the dome of the tent a sheen appeared, so thin and delicate that one had to ask one's head to the pain in the neck to see it. The thread that wasn't there shimmered like a cobweb after the first frost.

Nela felt she had to get up, even though she knew she mustn't. She raised herself a little, enough to see better. The programme in her hands warmed up as if from the sun. On the edge of the sheet of paper inked with herself, she crossed out a new word: "Listen."

She closed her eyes only for a fraction of a second to catch her breath. When she looked up again, the spotlight was no longer solitary. A second beam, warmer, spilled across the canvas of the tent, and a shadow appeared against the white background. A shadow that belonged to neither of them, for it moved differently, like someone stepping over something very thin and important. The shadow leaned over, as if checking the tying of a shoe, and straightened up gracefully. Oskar drew in air violently.

- 'Nela,' he whispered. - Something is coming.

The snare drum accelerated, the steel strings groaned as if they remembered they were strings. Up top, where nothing should be, the dust hung in one place and trembled. Nela leaned forward another millimetre. She felt the whole tent - the audience, the orchestra, the director in the lilac cylinder - hold its breath along with her.

And then above the arena, just above the brightest point of light, a delicate, silvery rope that had not been there before trembled and bent barely perceptibly, as if under the weight of someone's foot.

Autor zakończenia:

English

English

polski

polski

Co było dalej?

Co było dalej?